ARTICLE – FEBRUARY 2011

The Flexible Spirit of Gabriel Lester

by Nina Folkersma

published in Metropolis M, no 1, 2011

There he stands: the con artist, the artist-impostor who conjures something out of nothing and then manages to make money at it. Neatly attired in a suit, he converses with the gallery owner, holding a glass of wine. The supple way he moves and his relaxed hand gestures show how completely at ease he is in the art world. He is a professional, charming and self-assured. I recognize him from Gabriel Lester’s 2007 film, Untitled Incident, by his small black moustache. It is the artist himself, maker of short and not-so-short films, performances and installations at art centres and works in public space. Lester is an artist who excels in pretending, in creating illusions. In Untitled Incident, the seductive charmer ultimately proves to have less control of his own behaviour than he would have us believe. With its rapid hand gestures, lack of dialogue and breezy piano music in the background, the film makes a slapstick impression. With this, as if it were obvious, Lester was referring back to himself. As an artist, what is the role that Gabriel Lester plays?

Mime

The first time I saw Gabriel Lester’s work was in 1999, at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. That installation, entitled How to Act, was also the first installation that he had created in his role as artist. Prior to that, he already had something of a career behind him, as a music producer, writer and director for video clips. At the Rijksakademie, in a simple white space, Lester covered the ceiling with dozens of coloured lights. Beneath them we heard a soundtrack. The bundles of light moved to the rhythm, or better said, to the atmosphere of the music. To a romantic melody, the lights danced in pink. To ascending, threatening music, they moved like storm warnings, and so on, the lights magically evoking all kinds of imaginary film scenes. Gabriel Lester is fascinated by the simplicity with which an illusion can be created. For the same reason, he is also extremely fond of old film genres, slapstick and mime. In these genres or techniques, the way we are led down the garden path is often completely obvious, but we fall for it anyway. That is the magic.

When I visit Lester to speak with him about his solo exhibition at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, he describes a poignant, youthful memory of a dramatic scene. Standing in an improvised little theatre are two men (one of whom is his father), who are performing a pantomime with an imaginary apple. The men are waiting at a bus stop, and while one leans forward to see if the bus is coming, the other removes an apple from his trouser pocket, takes a big bite and chews it, as surreptitiously as possible. Of course, as a child, Lester knew that the apple was not real, but he was all too happy to let himself be carried away by the power of suggestion. This ambiguity, this confusing game with perception, imagination and desire, had already kindled his fascination for the mechanisms with which our minds and spirits can be manipulated. Lester explains that his early installation at the Rijksakademie can best be understood as ‘a film in mime’. It illustrates how something that is unmistakably incomplete is completed in the mind of the viewer.[1]

Wishful thinking

At his first solo exhibition at the Boijmans Van Beuningen, How to Act will be presented again for the first time since then. Although he has often been asked to show the work again, Lester has thus far always hesitated to do so. As he explains, it is dangerous to get caught up in the success of your first work. Now he is ready to do it, but it will be in a new, expanded form.

The exhibition also includes a large number of new works. One of these is a film about lotteries, entitled The Big One. Lester gathers up a stack of books for me about the history of lotteries and shows me an old black-and-white film about a lottery draw in Oostende. Lotteries have for ages been true folk spectacles. In the old days, people from all walks of life streamed together in large arenas and watched the huge tombola at the centre with bated breath, just as they would a theatrical performance. Men in suits operated the rotating drums, filled with numbered balls, while an orchestra played appropriate music in the background and a number of specially selected children got to blindly pick the winning numbers.

The title, The Big One, is a reference to the name given in Spain to the annual, immensely popular, Christmas season lottery, El Gordo, or ‘the fat one’. This is unlike the Dutch state lotteries, where people do not choose their own numbers, or at best, can pick only the final cipher. In Spain, you can put together your own combination of numbers, such as astrological numbers, your own date of birth, that of your child, or your anniversary. According to Lester, purchasing a lottery ticket is a form of wishful thinking, not in the negative sense of something that is doomed to failure, but a hopeful and highly powerful form of thinking. We purchase a lottery ticket because we generally believe that this is our ticket to an untroubled, sunny existence. It is not a game. We are not merely gambling. By selecting the right numbers, the right place to buy them, the right day, the right clothes, we think that we can influence the future. In this sense, buying a lottery ticket is a symbolic attempt to take our destiny into our own hands and avoid fate.

Honest Lies

Those who are familiar with his spoken word performances know that Gabriel Lester is a quick, agile and convincing speaker. He regularly acts as emcee for performance evenings, revealing himself to be a consummate showman, commanding the expectations of his audiences. Last summer, I saw him together with artist Michael Portnoy, playing the clown during the Nacht van Duivenvoorde (Duivenvoorde Night, 26 June, 2010). During the meal, Lester ran alongside the long tables and occasionally climbed on them to serve the public with a relatively incomprehensible speech, while otherwise pestering Portnoy, who was dressed in a clown costume. Another personality with whom Lester frequently collaborates is Raimundas Malasauskas, a curator who has built an international career with exhibitions centred on such concepts as illusion, magic, doppelgangers, poseurs, fakes and tricksters. Consistently permeating all of their projects is the questioning of every possible claim to reality.

Cautiously, I suggest to Lester that all this is not very critical or socially engaged. He is the first to agree. Raised in the 1970s in a left-wing commune in Groningen, he has had his dose of political engagement. It is not that he has backed away from society, but his affinities and competencies lie elsewhere. In his three-dimensional installations, for example, in which he uses long, thin slats to obstruct our view of an interior, he expressly plays with our consciousness of reality and our belief in the illusion. We can never see the space in its entirety. Through the slats, we see only cut-outs, yet in our minds, we still turn them into a whole, as if they were successive scenes in a film. Here too, it is the simplicity that so enthrals him.

We could refer to the way Gabriel Lester works as ‘honest lying’. Or, as he himself says, ‘It is much like a simple magic trick shown and then explained…. In the case of my installations and films, both the illusion and the mechanism remain, and this is one of the things that I find interesting: when one understands the mechanism, and still, one can’t get the taste (the initial charm) of the magic and the illusion out of one’s mind.’[2]

Suspension of Disbelief

At the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum, in addition to his new film, The Big One, Gabriel Lester will also present a new series of works about meteorites. In recent months, he has collected hundreds of images from the Internet, by people who have found a piece of meteorite, or who have sometimes even literally been struck by them. How great is the chance that anyone would ever be hit by a meteorite, a falling star? When it happens, is it a sign of luck or of disaster?

Lester presents his exhibition as a total installation, with interventions, films, sculptures and random objects, in which all of the works circle around one another and loosely refer to one another. He has given the exhibition the suitable title, Suspension of Disbelief. The term is primarily used in cinema and refers to the willingness of the audience to accept reality as it is presented or sketched in the film, even when it is not real at all and all of the laws of logic are being openly mocked. This is, of course, exactly what Lester expects of his own audience. But do we agree with him?

It remains difficult to pin Gabriel Lester down to a clear position. Is he the illusionist, the charming Don Juan, the smooth-talking entertainer, or is he the philosophical artist who stimulates our thinking about reality? There is a considerable amount of posing in his work, and nothing is more complicated than a pose. Gabriel Lester is always to be found somewhere between truth and illusion, between really knowing and pretending to know. His work demands a great deal of flexibility from our human mind. Is it, I ask, about training the flexibility of our spirit? ‘Flexibility of the Spirit’, replies Lester, ‘that sounds good. That is a term I have not heard for a long time. You could use that as a title for your article.’

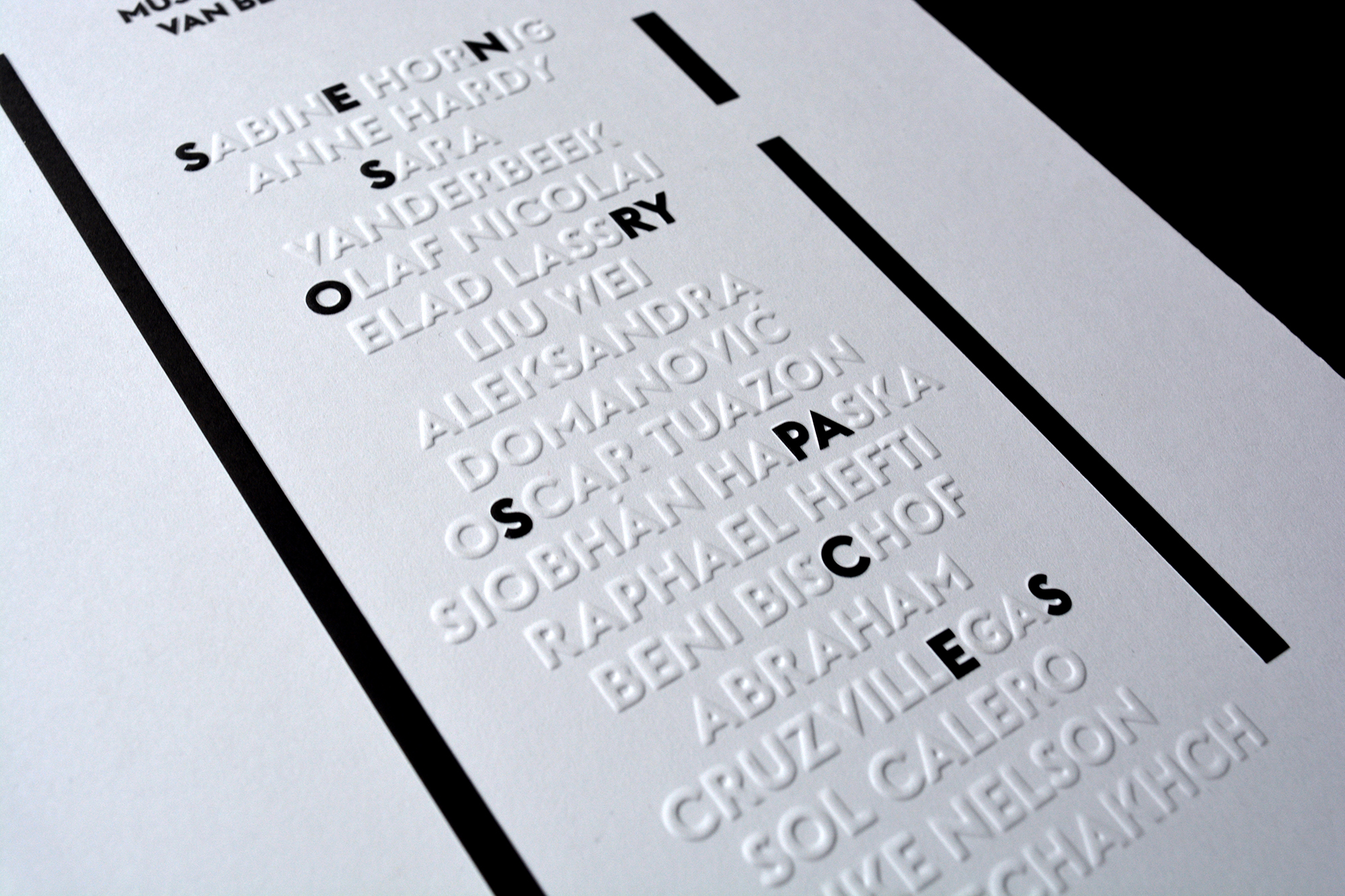

Gabriel Lester: Suspension of Disbelief

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

12 February – 8 May, 2011

[1] Graham Gussin, A Conversation, published at www.gabriellester.com

[2] Idem

Translated from the Dutch by Mari Shields